AUSTIN AHMASUK, Appellant,

v.

STATE OF ALASKA, DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, COMMUNITY & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, DIVISION OF BANKING & SECURITIES, Appellee.

Counsel: Susan Orlansky, Reeves amodio LLC, Anchorage, for Appellant.

Robert H. Schmidt, Assistant Attorney General, Anchorage, and Kevin G. Clarkson, Attorney General, Juneau for Appellee.

Jahna M. Lindemuth, Holmes Weddle & Barcott, PC, Anchorage, for Amici Curiae Bristol Bay Native Corporation; Calista Corporation; Cook Inlet Region, Inc.; and Doyon Limited.

Judges: Winfree, Stowers, Maassen, and Carney, Justices. [Bolger, Chief Justice, not participating.].

Winfree

OPINION

I. INTRODUCTION

The Alaska Division of Banking and Securities civilly fined Sitnasuak Native Corporation shareholder Austin Ahmasuk for submitting a newspaper opinion letter about Sitnasuak’s shareholder proxy voting procedures without filing that letter with the Division as a shareholder proxy solicitation. Ahmasuk filed an agency appeal, arguing that the Division wrongly interpreted its proxy solicitation regulation to cover his letter and violated his constitutional due process and free speech rights. An administrative law judge upheld the Division’s sanction in an order that became the final agency decision, and the superior court upheld that decision in a subsequent appeal. Ahmasuk raises his same arguments on appeal to us. We conclude that Ahmasuk’s opinion letter is not a proxy solicitation under the Division’s controlling regulations, and we therefore reverse the superior court’s decision upholding the Division’s civil sanction against Ahmasuk without reaching the constitutional arguments.

II. BACKGROUND

A. State Laws And Regulations Relevant To Alaska Native Corporations

Corporations authorized by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA)[1] are incorporated under the Alaska Corporations Code.[2] ANCSA explicitly exempts ANCSA corporations from federal securities regulation compliance,[3] and the Division therefore regulates certain activities of specified ANCSA corporations and their shareholders and investigates complaints of illegal conduct.[4]

The dispute in this appeal — involving ANCSA corporation shareholder voting and proxy solicitation — requires an initial consideration of relevant Alaska corporations code statutes,[5] Alaska securities regulation statutes,[6] and regulations promulgated by the Division in its role as regulator of ANCSA corporations’ shareholder election activities.[7] We begin with shareholder voting, move next to shareholder voting by proxy, and then conclude with solicitation of shareholder proxies.

1. Shareholder voting

Generally, subject to variation in a corporation’s articles of incorporation, a shareholder has the right to one vote per share owned and to “vote on each matter submitted to a vote at a meeting of shareholders.”[8] And with respect to electing members to a board of directors, again unless the articles of incorporation provide otherwise, a shareholder may “cumulate votes,”[9] i.e., may vote “the number of shares owned by the shareholder for as many persons as there are directors to be elected,” giving one candidate all votes or distributing votes among candidates as the shareholder deems appropriate.[10] For example, a shareholder with 100 shares of stock voting in an election of 4 members to the board of directors would have 400 votes to cast, either all for 1 candidate or divided among the candidates in any way the shareholder chooses.

2. Shareholder proxy voting

Generally, a “person entitled to vote shares may authorize another person or persons to act by proxy with respect to the shares.”[11] The term “proxy” is statutorily defined in simple fashion as “a written authorization . . . signed by a shareholder . . . giving another person power to vote with respect to the shares of the shareholder.”[12]

By statute the Division regulates certain ANCSA corporation and shareholder election activities.[13] The Division has promulgated two relevant regulations about proxies. First, the Division has construed “proxy” more expansively than the corporations code by defining it as “a written authorization which may take the form of a consent, revocation of authority, or failure to act or dissent, signed by a shareholder . . . and giving another person power to vote with respect to the shares of the shareholder.”[14] Second, the Division has established specific substantive proxy rules.[15] For example, the relevant regulation provides that one who holds a proxy “shall vote in accordance with any choices made by the shareholder or in the manner provided by the proxy when the shareholder has not specified a choice.”[16] With respect to electing directors, that regulation also describes how a proxy document must present the shareholder with voting choices[17] and provides that “if the shareholders have cumulative voting rights, a proxy may confer discretionary authority to cumulate votes.”[18]

Discretionary cumulative proxy voting is the underlying issue of this litigation. As described above, if a corporation allows cumulative voting in director elections, a shareholder will have the same multiple of votes per share as there are director candidates; the shareholder may, in the shareholder’s sole discretion, allocate those votes among the director candidates in any manner.[19] How does this work with respect to proxy voting in ANCSA corporations’ director elections? A proxy holder ultimately must vote the shareholder’s shares as directed by the shareholder.[20] But a proxy form may provide for a shareholder to grant the proxy holder the same discretionary cumulative voting authority held by the shareholder.[21] The proxy form must set out options and instructions for the shareholder to direct the proxy holder how the shares should be voted for individual director candidates.[22] And the proxy form must set out the proxy holder’s authority to vote the shareholder’s shares in the event the shareholder fails to designate how the shares are to be voted.[23]

3. Proxy solicitation regulation

Particularly relevant to this appeal, the Division regulates share holder proxy solicitations for some ANCSA corporations: proxy solicitation materials, including proxies and proxy statements,[24] must be filed with the Division and may not contain false material facts (or omit facts necessary to keep a statement from being misleading).[25] The Division defines “solicitation” as “a request to execute or not to execute, or to revoke a proxy” and alternatively as the “distributing of a proxy or other communication to shareholders under circumstances reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding, or revocation of a proxy.”[26]

B. Sitnasuak Proxy Voting

Sitnasuak, headquartered in Nome, is the largest ANCSA village corporation in the Bering Straits region and is subject to Division regulation. Sitnasuak has almost 2,900 shareholders and an 11-member board of directors. Sitnasuak allows cumulative voting — shareholders thus may cast their cumulated votes for one director candidate or distribute votes among some or all director candidates[27] — and its shareholders may vote for directors either in person or by proxy.[28] Accordingly, Sitnasuak may, and does, allow discretionary proxy voting.[29]

Discretionary proxy voting in director elections has been the subject of Sitnasuak shareholder debate for at least the last few years. Sitnasuak’s bylaws provide for a special shareholders’ meeting when holders of 10% of its voting stock request it, and in 2015 a sufficient number of Sitnasuak shareholders petitioned for a special shareholders’ meeting to discuss eliminating discretionary proxy voting. Notice of the special shareholders’ meeting was given in December 2015, and the meeting convened in early January 2016. A proposal to amend Sitnasuak’s articles of incorporation to eliminate discretionary proxy voting in director elections was explained to the attendees. But a required voting quorum could not be established; the remainder of the meeting was considered informational only, and the parliamentarian made a presentation about cumulative and proxy voting.

Soon thereafter Sitnasuak issued a newsletter discussing the special shareholders’ meeting and setting out a written version of the parliamentarian’s discussion of cumulative and proxy voting. Sitnasuak’s newsletter advocated for discretionary proxy voting, with the following statements:

Many shareholders believe that the Board of Directors use discretionary and cumulative voting to keep their power by reelecting themselves or others. While a discretionary proxy can have that result, it is also used by shareholders who believe they are in a minority to elect someone to voice their interests on the board. . . . However, electing a minority member to a board can be difficult. Most shareholders can only attend a meeting by proxy. This means that they won’t know which candidates running for a board will have enough votes to be elected. This happens when shareholders . . . vote directed proxies and others vote discretionary proxies. Directed votes can’t be changed. A candidate who does not get enough directed votes to win still uses up the directed vote. It can’t be transferred to another candidate.

….

…Shareholders who are able to attend a meeting in person have the opportunity to change their votes and help a candidate who doesn’t have enough proxy votes to potentially be elected to a board seat. That’s also what a proxy holder can do with a discretionary proxy. If four candidates run together on one proxy, and only one has enough directed votes to give them a chance of winning a board seat, then a discretionary proxy can mean the difference between electing a minority candidate to the board, or not. Eliminating discretionary voting removes the possibility for this to happen. Of course this means that the majority can also use discretion to assure election of a maximum number of majority directors. Shareholders who support minority candidates don’t like this outcome, but it’s just fair.

. . . .

While discretionary voting is controversial, if it is applied fairly, it has benefits for all shareholders.

C. Ahmasuk’s Letter And The Complaint

In early February 2017 — well before Sitnasuak’s annual shareholders’ meeting and at least two months before any director candidates were announced or any election-related materials were distributed to shareholders — Ahmasuk submitted the following opinion letter published in the Nome Nugget:

Dear Editor, The Village Corporation for Nome i.e. Sitnasuak Native Corporation (SNC) will soon be holding its annual election and shareholders will file for candidacy. SNC's shareholders have voiced time and time again that they do NOT want discretionary proxies used. Discretionary proxies are NOT required by any Alaskan law and there is NO law that prohibits an ANCSA corporation from prohibiting them for elections. Hundreds of SNC shareholders have said through public letters, social media, or through mailings that they do NOT want discretionary proxies used for elections. I believe SNC shareholders are realizing that discretionary proxies are harmful to our election process and are realizing in greater numbers such practices are disrespectful to our traditions. In 2015 and 2016 I and others spent many hours collecting signatures for a request for a special meeting to do away with discretionary proxies. We collected hundreds of signatures and we met a 10% requirement as required by Alaskan law to petition the SNC Board of Directors to consider doing away with discretionary proxies and to request a special meeting. You might ask yourself why all this commotion about discretionary proxies? Because I and others have thoroughly researched the issue and recognized there is a dramatic ethical argument about what is right and what is wrong with SNC's elections. Discretionary proxies have allowed single persons to use discretionary proxies to dramatically alter the outcome of an election for their singular goal. You know who they are they are members of the SNC 6. Please do NOT vote a discretionary proxy in 2017. Thank you[.] (Emphases in original.)

A Sitnasuak director complained to the Division that Ahmasuk’s letter was a proxy solicitation seen by more than 30 people.[30] The director alleged that Ahmasuk therefore had violated proxy solicitation regulations by (1) not concurrently filing required disclosures with the Division[31] and (2) making false and misleading statements about discretionary proxy use.[32]

D. Administrative Proceedings And Division Decision

The Division notified Ahmasuk of the complaint, later asking him whether he had filed his letter with the Division and whether he could support his substantive assertions about proxy voting. Ahmasuk responded that the proxy regulations did not apply because his letter was published prior to candidate and proxy announcements for the upcoming election. Ahmasuk also contended that the regulations are nebulous and that the investigation violated his First Amendment free speech right. Ahmasuk said that, based on his personal experience and assessment of past elections, he believed his statements, including his contention that discretionary proxies allowed individuals to alter election outcomes, were factual.

In mid-March — still before any director candidates were announced or any annual meeting election-related materials were distributed to shareholders — the Division issued an order concluding that Ahmasuk’s letter was a proxy solicitation requiring AS 45.55.139 disclosures. The Division’s order stated that Ahmasuk thus had violated 3 AAC 08.307 by failing to file a copy of the letter with the Commissioner and 3 AAC 08.355 by failing to file required disclosures. The Division also concluded that Ahmasuk had violated 3 AAC 08.315(a) by making the material misrepresentation that discretionary proxies have allowed individuals to alter election outcomes. The Division ordered Ahmasuk to pay a $1,500 civil penalty and to comply with Alaska securities laws and regulations.

Ahmasuk appealed the order, requesting a hearing and that the order be set aside.[33] He listed three grounds for setting aside the decision, arguing that his letter was: (1) protected by the First Amendment as political speech; (2) not a proxy solicitation; and (3) not false or misleading. The parties agreed to address as a threshold matter whether Ahmasuk’s letter was a proxy solicitation subject to regulation and to allow appellate proceedings to conclude on that issue before later, if necessary, addressing whether Ahmasuk’s letter contained a material misrepresentation.

Ahmasuk sought summary adjudication on the proxy solicitation question. The thrust of Ahmasuk’s argument was that his letter could not qualify as a proxy solicitation because it “was not ‘reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding, or revocation of a proxy.'” Ahmasuk contended that a reasonable reading of the proxy solicitation regulation “does not alert a shareholder that [it applies] to public statements about the election process in general . . . when no candidates have been announced, no individuals . . . are asking shareholders to sign proxies . . . , and no shareholder vote on a particular matter is scheduled.” Ahmasuk also contended that if the proxy solicitation regulation covered his letter, the regulation would violate his constitutional due process and free speech rights.

Following briefing and oral argument, the Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) upheld the Division’s order. The ALJ’s decision noted the following undisputed facts: Ahmasuk’s letter was written two months before the identification of candidates and five months before the election; his letter did not explicitly advocate for or against any distinct outcome of the election; and his letter urged shareholders not to vote by discretionary proxy. The ALJ focused on one sentence from the letter — “Please do NOT vote a discretionary proxy in 2017” (emphasis in original) — noting the Division’s agreement at oral argument “that the letter would not constitute a proxy solicitation if it did not include [that] sentence.”

The ALJ ultimately concluded that the sentence in Ahmasuk’s letter fit within the regulatory definition of a proxy solicitation because it was “both a direct request to not execute a discretionary proxy, as well as a communication reasonably calculated to result in the withholding of a discretionary proxy.” The ALJ rejected Ahmasuk’s free speech challenge, noting that “Ahmasuk did not stop at simply communicating his position — he requested that . . . shareholders not vote a discretionary proxy.” The ALJ also rejected Ahmasuk’s due process challenge, quoting the regulation and stating that “[i]t seems reasonable that a reader of this regulation would understand that an actual request to withhold a type of vote, as in . . . Ahmasuk’s letter, falls within the definition.” The ALJ’s decision ultimately became the Division’s final decision.[34]

E. Superior Court Proceedings

Ahmasuk appealed to the superior court, reiterating his legal arguments. The superior court first rejected Ahmasuk’s argument that the proxy solicitation regulation cannot apply absent identifiable candidates, proxy forms, and an election. The court concluded that the “regulatory scheme provides for broad application” and that Ahmasuk’s interpretation would defy common sense and the regulation’s plain language.

The superior court next rejected Ahmasuk’s argument that the regulation, as applied, violated his constitutional right to due process. The court reasoned that the regulatory language defining solicitation as “distributing . . . communication to shareholders under circumstances reasonably calculated to result in the . . . withholding . . . of a proxy” offered fair notice that communicating with shareholders and urging them to withhold proxies could be deemed a proxy solicitation. The court contrasted Ahmasuk’s concern “that under a broad and inclusive reading of . . . solicitation every disparaging comment by a shareholder will be treated as a proxy statement because it might influence a shareholder vote,” with his letter “specifically referencing the upcoming election, specifically urging sharehold[ers] to withhold a proxy.” The court concluded that the regulations were clear, instructive, and provided fair notice that a statement like Ahmasuk’s letter could be considered a proxy solicitation and that failure to register merited a fine.

The superior court also rejected Ahmasuk’s argument that the Division’s application of the proxy solicitation regulations violated his freedom of speech. Noting the government’s compelling interest in regulating election integrity and citing case law suggesting proxy solicitation regulations do not violate the constitution’s free speech guarantee,[35] the court concluded that even statements not advocating for or against a particular candidate may be regulated as proxy solicitations.

F. Appeal

Ahmasuk appeals the superior court’s decision. The Division’s position is supported by amici curiae Bristol Bay Native Corporation, Calista Corporation, Cook Inlet Region, Inc., and Doyon Limited. Sitnasuak did not participate in the Division proceedings, the superior court appeal, or this appeal.

III. STANDARD OF REVIEW

“When the superior court has acted as an intermediate court of appeal, we review the merits of the administrative agency’s decision without deference to the superior court’s decision.”[36] The parties dispute which standard of review should govern our consideration of the Division’s regulatory interpretation and conclusion that Ahmasuk’s letter was a proxy solicitation. The Division and Amici argue that we should employ a deferential standard of review for this threshold question. Ahmasuk argues that we should not defer to the Division’s interpretation of the regulations.

We generally employ the following standards of review when considering an agency action based on its interpretation of its statutory directives and regulations:

We apply the reasonable basis standard to questions of law involving "agency expertise or the determination of fundamental policies within the scope of the agency's statutory functions." When applying the reasonable basis test, we "seek to determine whether the agency's decision is supported by the facts and has a reasonable basis in law, even if we may not agree with the agency's ultimate determination." We apply the substitution of judgment standard to questions of law where no agency expertise is involved. Under the substitution of judgment standard, we may "substitute [our] own judgment for that of the agency even if the agency's decision had a reasonable basis in law." . . . We review an agency's interpretation and application of its own regulations using the reasonable basis standard of review. "We will defer to the agency unless its 'interpretation is plainly erroneous and inconsistent with the regulation.'" "We give more deference to agency interpretations that are 'longstanding and continuous.'"[37]

Because our conclusion would be the same regardless of the standard of review, we express no opinion on the parties’ disagreement. We explain our decision using the more deferential standard.

IV. DISCUSSION

The fundamental question before us is whether the Division’s interpretation and application of its definition of “solicitation,” as it relates to the definition of “proxy,” is reasonable under the facts and circumstances of this case. Both the statute and the Division’s regulations define “proxy” as “a written authorization . . . signed by a shareholder . . . giving another person power to vote” the shareholder’s shares.[38] The regulations also provide that the written document “may take the form of a consent, revocation of authority, or failure to act or dissent.”[39]

For our purposes, then, a proxy is a written authorization or consent, or a written revocation of an authorization or consent, for someone to vote a shareholder’s shares. This is reinforced by 3 AAC 08.365(16)’s two-pronged definition of proxy “solicitation”: under (A), “a request to execute or not to execute, or to revoke a proxy”; and under (B), a “communication to shareholders . . . reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding, or revocation of a proxy” (emphasis added). We are concerned only with a putative solicitation of a proxy execution or revocation for Sitnasuak’s 2017 director election.[40]

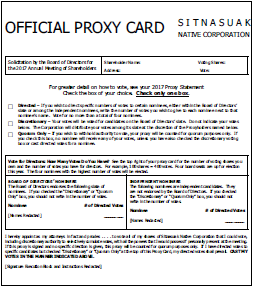

With this in mind, to see how a Sitnasuak shareholder would execute and make a designation for directed or discretionary voting on a proxy card solicited by Sitnasuak’s board of directors months after Ahmasuk’s opinion letter, Sitnasuak’s official proxy card for the June 2017 annual shareholder meeting’s election of four directors is reproduced, in relevant part, below.

We also note that in May 2017, after the initiation of the enforcement action underlying this appeal, three Sitnasuak shareholders, including the Sitnasuak director who filed the complaint against Ahmasuk, solicited proxies to vote for themselves as directors at the 2017 annual meeting. This group’s proxy card was designated a “Discretionary Proxy Card” and conferred authority to use discretionary cumulative voting to elect as many of the three shareholders “as [a] proxy holder decides is appropriate.” But the card instructed that a shareholder could withhold authority to vote for one or more of the three candidates by striking out the candidate’s name, and, of course, a shareholder also could have specified how to allocate the votes.[41] This proxy card is set out in relevant part below.

Independent Shareholder Solicited Discretionary Proxy Card

For the Sitnasuak Native Corporation Annual Meeting of Shareholders

I appoint [Names Redacted] with full power of substitution, to represent me as my proxy and to vote my shares in accordance with the instructions in this document at the [June 2017] Annual Meeting of Shareholders of Sitnasuak Native Corporation . . . and at any adjournment thereof.

INSTRUCTIONS TO PROXY HOLDER

For the election of directors, my proxy holder is instructed to cumulate and distribute my votes among the following people, to elect as many to the Sitnasuak Native Corporation Board of Directors as my proxy holder decides is appropriate.

[Names Redacted]

(You may withhold authority to vote for a nominee by lining through or otherwise striking out the name of that nominee).

For other matters, my proxy holder is given discretionary authority to vote my shares on matters incident to the conduct of the meeting and on any other matter, not specifically addressed by this proxy, which may properly come before the meeting.

I have received the Sitnasuak Native Corporation 2016 Annual Report and the Notice of Annual Meeting & Proxy Statement dated April 7, 2017, and a Supplemental Proxy Statement from the proxy holder named above.

[Signature Execution Block Redacted]

[Proxy Submission Instructions Redacted]

As we analyze the Division’s application of its proxy solicitation regulation to Ahmasuk’s opinion letter, context is key. The important contextual backdrop in this case is the longstanding corporate governance debate about Sitnasuak’s allowing discretionary cumulative proxy voting for corporate director elections. How are shareholders supposed to debate the issue without what the Division contends is a “communication to shareholders . . . reasonably calculated to result in . . . withholding” some future proxy?[42] For example, how could a group of Sitnasuak shareholders even have prepared and submitted a petition for a corporate charter change eliminating discretionary cumulative voting for directors without coming within the Division’s broad interpretation of its solicitation definition? To avoid penalties, must such petition communications and related statements asking shareholders to use direct and not discretionary proxy forms be filed with the Division as a proxy solicitation, along with other burdensome requirements? Surely not.

For example, compare Ahmasuk’s letter with Sitnasuak’s newsletter. Both reference the shareholder debate about discretionary proxy voting. And both reference dissatisfied shareholders’ efforts to call a special shareholders’ meeting for a vote on eliminating discretionary proxy voting. With respect to the effect of discretionary proxy voting, Sitnasuak said:

Directed votes can't be changed. . . . . . . . . . . Shareholders who are able to attend a meeting in person have the opportunity to change their votes and help a candidate who doesn't have enough proxy votes to potentially be elected to a board seat. That's also what a proxy holder can do with a discretionary proxy. (Emphasis added.)

Consistent with Sitnasuak's statement, but using different terms about discretionary proxy holders being able to change votes to get a desired result, Ahmasuk said: "Discretionary proxies have allowed single persons to use discretionary proxies to dramatically alter the outcome of an election for their singular goal."

Under the Division’s regulatory interpretation, Sitnasuak’s newsletter could be seen as reasonably calculated to result in the eventual procurement of a future discretionary proxy card, or at least the eventual box-check for discretionary proxy voting on the corporate proxy card. The record reflects that Sitnasuak did not file its newsletter with the Division when it was circulated to shareholders and that Sitnasuak faced no enforcement action by the Division. Indeed, the ALJ noted that “[t]he Division’s interpretation at oral argument appear[ed] at odds with other Division decisions on the same issue,” lending credence to Ahmasuk’s argument that the regulation was “subject to inconsistent enforcement.”

The federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), when defining solicitation, considered the impact of excessive proxy solicitation regulation on corporate governance debate.[43] Because the Division apparently adopted the SEC’s then-existing solicitation definition when promulgating the Division’s definitions regulation,[44] the SEC definition’s history provides insight. In 1935 the SEC first defined solicitation to include any “request for a proxy, consent, or authorization, or the furnishing of any form of proxy.”[45] In 1938 the SEC amended the definition to include any proxy request, regardless whether “accompanied by or included in a written form of proxy.”[46] In 1942 the SEC revised the definition to include any request “reasonably calculated to” cause a shareholder to execute, not to execute, or to revoke, a proxy.[47]

Most pertinent to this case, in 1956 the SEC definition expanded to include “furnishing of a form of proxy or other communication to security holders under circumstances reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding, or revocation of a proxy.”[48] In adopting what essentially is a parallel provision to 3 AAC 08.365(16),[49] the SEC primarily was targeting communications by those who intended to solicit or already had solicited proxies before formally beginning solicitation.[50] The SEC apparently was seeking “to address abuses by persons who were actually engaging in solicitations of proxy authority in connection with election contests.”[51]

But the SEC later acknowledged its “proxy rules ha[d] created unnecessary regulatory impediments to communication among shareholders and others and to the effective use of shareholder voting rights.”[52] The SEC was concerned that the solicitation definition, too broadly construed, could “turn almost every expression of opinion . . . into a regulated proxy solicitation.”[53] It recognized that excessive regulation had “a chilling effect on discussion of management performance”[54] and raised First Amendment free speech concerns, particularly in regulating persons who are not in fact soliciting proxy authority.[55] The SEC clarified that when it adopted the 1956 definition it did not intend to regulate “persons who did not ‘request’ a shareholder to grant or to revoke or deny a proxy, but whose expressed opinions might be found to have been reasonably calculated to affect the views of other shareholders positively or negatively toward a particular company and its management or directors.”[56] Thus in 1992, to better achieve the proxy regulations’ purposes, the SEC adopted amendments significantly narrowing the “excessive regulatory reach of ‘solicitation.'”[57]

We share similar concerns about this case, namely that the Division’s broad regulatory interpretation contravenes the proxy regulations’ purposes and stifles corporate governance debate. If the solicitation regulation can cast such a wide net that it applies without regard to whether there actually is a pending election with known director candidates and proxy cards circulating (or known to be circulating imminently) for shareholder signatures, then the regulation may well go beyond valid regulation and into free speech infringement.[58]

And it would be difficult to enforce even-handedly. For example, the Division conceded it has no regulatory interest in whether an ANCSA corporation shareholder votes in person or by proxy in director elections, and presumably the Division has no regulatory interest in whether an ANCSA corporation allows or disallows discretionary cumulative voting in director elections. But the Division responded to our questioning at oral argument by saying that it would be a “technical” violation — apparently meaning unlikely to be enforced — if a shareholder communicated a general desire that all shareholders attend an annual meeting in person rather than give someone a proxy. There are few shades of gray between that hypothetical and Ahmasuk’s communicated general desire that, if a shareholder grants a proxy, it should be a directed rather than discretionary proxy.[59]

Consider again the undisputed facts of this case. Ahmasuk wrote his letter in February; Sitnasuak’s annual shareholder meeting was not held until the summer. Although in February shareholders knew that an annual shareholder meeting and director election would take place sometime in the future, no director candidates had been announced, no required corporate or other election-related disclosures had been circulated, and no proxy cards had been circulated. Because no proxy card was available — or known to be soon available — for shareholders’ execution, nothing concrete existed for Ahmasuk to ask a shareholder to execute, not execute, give, or withhold.[60] And Ahmasuk was neither running as a director candidate nor asking to be a proxyholder.

To the extent the Division viewed Ahmasuk’s opinion letter as directed at a specific proxy card, it could have been only the expected annual Sitnasuak official proxy card.[61] As discussed, the allegedly offending sentence in Ahmasuk’s letter was a request that shareholders “NOT vote a discretionary proxy.” (Emphasis in original.) But Sitnasuak’s proxy card is no more a “discretionary proxy card” than it is a “directed proxy card”; it allows a shareholder to check a box for either form of voting. The proxy card must be filled out with a shareholder’s instructions and then executed; Ahmasuk did not ask that the upcoming Sitnasuak proxy card be executed, not executed, given, or withheld; he effectively asked only that shareholders not check the discretionary proxy voting box.[62] In the context of this case, and at its broadest, the solicitation regulation governs only seeking the execution or non-execution of a proxy.[63] If the Division predicated its enforcement action on Ahmasuk’s statement being directed to the then unissued Sitnasuak official proxy card, the Division’s solicitation definition does not seem to cover his statement.

And the Division’s interpretation appears to conflict with its regulations describing the effect of “withholding a proxy.” Although the term is not expressly defined, a regulation describing proxy requirements clearly explains what must be provided on a proxy form for director elections:

(A) a box opposite the name of each nominee which may be marked to indicate that authority to vote for that nominee is withheld; (B) an instruction that the shareholder may withhold authority to vote for a nominee by lining through or otherwise striking out the name of that nominee; . . . .[64]

The term “proxy” refers to “a written authorization . . . to vote”;[65] regulatory language describing “withhold[ing] authority to vote” on a physical proxy card thus appears to describe at the voting level what it means to “withhold . . . a proxy” under 3 AAC 08.365(16)(B). And it refers to the act of not voting for a specific candidate by checking a box or “striking out the name of that nominee.” Ahmasuk’s opinion letter did not ask anyone to make or withhold specific votes in a proxy card.

This is a logical interpretation when compared to the other acts listed in 3 AAC 08.365(16), as striking out a specific nominee’s name — i.e., voting against that candidate — would be the direct inverse of “procur[ing]” or “execut[ing]” the authority to vote for a specific candidate. Any broader reading would lead to absurd results. Again, would Ahmasuk have violated these provisions if, for example, he instead had implored shareholders to simply vote in person? If not, why would imploring shareholders to vote by directed proxy rather than discretionary proxy have a different result? Although the ALJ noted that “any proxy type may significantly affect an election,” impact alone does not constitute a proxy solicitation.

The Division’s interpretation and application of its proxy solicitation regulation are unreasonable on the facts of this case.[66] Without reaching the constitutional issues Ahmasuk raises, we reverse the superior court’s decision upholding the Division’s order sanctioning Ahmusuk. We remand to the superior court to dismiss the Division’s complaint against Ahmasuk and to reevaluate prevailing party status for purposes of an attorney’s fees award.[67]

V. CONCLUSION

We REVERSE the superior court’s decision upholding the Division’s order sanctioning Ahmasuk and REMAND for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Footnotes

1Pub. L. No. 92-203, §§ 7-8, 85 Stat. 688, 691-94 (1971) (codified as amended at 43 U.S.C. §§ 1606–1607 (2020)) (authorizing creation of Alaska-chartered regional and village native corporations).↑

2AS 10.06.960-.961 (providing that corporations organized under ANCSA are subject to corporations code provisions, with specified overriding exceptions).↑

4See, e.g., AS 45.55.139 (limiting coverage to ANCSA corporations with 500 or more shareholders and total assets exceeding $1,000,000); AS 45.55.910(a)(1) (authorizing Division to conduct investigations to determine whether “any provision of this chapter or a regulation or order under this chapter” has been or will be violated); 3 Alaska Administrative Code (AAC) 08.307 (2020) (governing ANCSA corporation proxy solicitation filings); 3 AAC 08.360 (detailing filing process); see also Henrichs v. Chugach Alaska Corp., 260 P.3d 1036, 1044 (Alaska 2011) (stating that ANCSA corporations are subject to Alaska proxy regulations but not federal proxy regulations). See generally AS 45.55.138-.990 (“Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act Corporations Proxy Solicitations and Stock”); 3 AAC 08.305-.365 (“Alaska Native Claims Act Corporations: Solicitation of Proxies”).↑

5See generally AS 10.06.005-.995 (“Alaska Corporations Code”).↑

6See generally AS 45.55.138-.990 (“Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act Corporations Proxy Solicitations and Stock”).↑

7See generally 3 AAC 08.305-.365 (“Alaska Native Claims Act Corporations: Solicitation of Proxies”).↑

8AS 10.06.420(a).↑

9Rude v. Cook Inlet Region, Inc., 322 P.3d 853, 856-57 (Alaska 2014).↑

10AS 10.06.420(d).↑

11AS 10.06.418(a); see also AS 10.06.420(c) (permitting shareholder voting in person or by proxy); AS 10.06.420(d) (permitting proxy voting in director elections).↑

12AS 10.06.990(34); see also Proxy, BLACK’S LAW DICTIONARY (11th ed. 2 019) (“Someone who is authorized to act as a substitute for another; esp., in corporate la w, a person who is authorized to vote another’s stock shares.”).↑

13See, e.g., AS 45.55.139 (requiring, for certain ANCSA corporations, that copies “of all annual reports, proxies, consents or authorizations, proxy statements, and other materials relating to proxy solicitations distributed, published, or made available by any person . . . shall be filed with the [Division] concurrently with its distribution to shareholders”); AS 45.55.160 (“A person may not, in a document filed with the [Division] or in a proceeding under this chapter, make or cause to be made an untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they are made, not misleading.”); AS 45.55.910(a)(1) (authorizing Division to conduct investigations to determine whether “any provision of this chapter or a regulation or order under this chapter” has been or will be violated); see generally AS 45.55.138-.990 (“Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act Corporations Proxy Solicitations and Stock”); 3 AAC 08.305 .365 (“Alaska Native Claims Act Corporations: Solicitation of Proxies”).↑

143 AAC 08.365(12).↑

15See 3 AAC 08.335.↑

163 AAC 08.335(b).↑

173 AAC 08.335(e).↑

183 AAC 08.335(g).↑

19See AS 10.06.420(d).↑

203 AAC 08.335(b).↑

213 AAC 08.335(f)-(g); see also Rude v. Cook Inlet Region, Inc., 322 P.3d 853, 857 (Alaska 2014) (“This regulation implies that a proxy must explicitly ‘confer’ the ‘discretionary authority to cumulate votes.'” (quoting 3 AAC 08.335(g))).↑

223 AAC 08.335(e).↑

233 AAC 08.335(d).↑

24The Division’s definitions regulation provides that a “proxy statement” is “a letter . . . or other communication of any type which is made available to shareholders under circumstances reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding, or revocation of a proxy.” 3 AAC 08.365(14); see also Proxy Statement, BLACK’S LAW DICTIONARY (11th ed. 2019) (“An informational document that accompanies a proxy solicitation . . . .”).↑

25See AS 45.55.139 (requiring, for certain ANCSA corporations, that copies “of all annual reports, proxies, consents or authorizations, proxy statements, and other materials relating to proxy solicitations distributed, published, or made available by any person . . . shall be filed with the [Division] concurrently with its distribution to shareholders”); AS 45.55.160 (“A person may not, in a document filed with the [Division] or in a proceeding under this chapter, make or cause to be made an untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they are made, not misleading.”); 3 AAC 08.307 (regarding filing of proxy solicitation materials); 3 AAC 08.315 (prohibiting false or misleading statements in proxy solicitation materials); cf. 3 AAC 08.325 (prohibiting certain proxy solicitations); 3 AAC 08.345 (regarding proxy solicitations by board of directors); 3 AAC 08.355 (regarding proxy solicitations other than by board of directors); 3 AAC 08.360 (providing for Division’s investigation of complaints alleging proxy solicitation regulation violations).↑

263 AAC 08.365(16)(A)-(B). The second definition for “solicitation” is the same as that for “proxy statement.” Compare 3 AAC 08.365(16)(B), with 3 AAC 08.365(14).↑

27See supra notes 9-10 and accompanying text.↑

28See supra notes 11-12 and accompanying text.↑

29See supra notes 17-18 and accompanying text.↑

30See 3 AAC 08.360(a) (“A shareholder, director, or officer of a corporation subject to AS 45.55.139, aggrieved by an alleged violation of 3 AAC 08.305 – 3 AAC 08.365 may request that the [Division] investigate the alleged violation.”).↑

31See AS 45.55.139 (“A copy of all . . . materials relating to proxy solicitations distributed, published, or made available by any person to at least 30 Alaska resident shareholders of a corporation organized under . . . [ANCSA] that has total assets exceeding $1,000,000 and a class of equity security held of record by 500 or more persons shall be filed with the [Division] concurrently with its distribution to shareholders.”). Required disclosures include: the name and address of each participant joining in the solicitation; identification and description of the participant’s financial interests and activities within the corporation; identification of legal proceedings the participant is involved in adverse to the corporation; and methods used to solicit proxies, estimated solicitation expenses, and who would bear the expenses. 3 AAC 08.355.↑

32See AS 45.55.160 (“A person may not, in a document filed with the [Division] or in a proceeding under this chapter, make or cause to be made an untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they are made, not misleading.”); 3 AAC 08.315(a) (“A solicitation may not be made . . . that contains a material misrepresentation.”).↑

33See AS 45.55.920(d) (providing that before imposing penalty “the [Division] shall give reasonable notice of and an opportunity for a hearing”); AS 44.64.030(a)(39) (providing that Office of Administrative Hearings conduct hearing required under AS 45.55 relating to ANCSA corporation proxy solicitations).↑

34See AS44.64.060(e)-(f) (providing that Division retains discretion to adopt, revise, or reject ALJ decision within certain time limits, otherwise “the [ALJ’s] proposed decision is the final agency decision”).↑

35Meidinger v. Koniag, Inc., 31 P.3d 77, 84-85 (Alaska 2001).↑

36Studley v. Alaska Pub. Offices Comm’n, 389 P.3d 18, 22 (Alaska 2017) (quoting Tolbert v. Alascom, Inc., 973 P.2d 603, 606-07 (Alaska 1999)).↑

37Davis Wright Tremaine LLP v. State, Dep’t of Admin., 324 P.3d 293, 299 (Alaska 2014) (alteration in original) (footnotes omitted) (first quoting Marathon Oil Co. v. State, Dep’t of Nat. Res., 254 P.3d 1078, 1082 (Alaska 2011); then quoting Tesoro Alaska Petroleum Co. v. Kenai Pipe Line Co., 746 P.2d 896, 903 (Alaska 1987); then quoting id.; then quoting Kuzmin v. State, Commercial Fisheries Entry Comm’n, 223 P.3d 86, 89 (Alaska 2009); and then quoting Marathon Oil, 254 P.3d at 1082).↑

38AS 10.06.990(34); 3 AAC 08.365(12).↑

393 AAC 08.365(12).↑

40See 3 AAC 08.325(4)-(5) (prohibiting proxy solicitation conferring authority to vote “at more than one shareholders’ meeting or . . . at any shareholders’ meeting other than the one disclosed”).↑

41See 3 AAC 08.335(b), (e), (g); supra notes 20-22 and accompanying text.↑

423 AAC 08.365(16)(B).↑

43See Regulation of Communications Among Shareholders, 57 Fed. Reg. 48,276 (Oct. 22, 1992) (hereinafter 1992 Amendments).↑

44Compare 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-1(l)(1)(iii) (defining solicitation, in part, as “furnishing of a form of proxy or other communication to security holders under circumstances reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding or revocation of a proxy”), with 3 AAC 08.365(16)(B) (defining solicitation, in part, as “the distributing of a proxy or other communication to shareholders under circumstances reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding, or revocation of a proxy”).↑

45Exchange Act Release No. 34,378, 1935 WL 29270 (Sept. 24, 1935).↑

46Exchange Act Release No. 34,1823, 1938 WL 33169 (Aug. 11, 1938).↑

47See Exchange Act Release No. 34,3347, 1942 WL 34864 (Dec. 18, 1942).↑

48See Adoption of Amendments to Proxy Rules, Exchange Act Release No. 34,5276, 1956 WL 7757 (Jan. 17, 1956) (hereinafter 1956 Amendments).↑

49See supra note 44.↑

50See 1956 Amendments, supra note 48, at 34,5277 (“[S]tatements made for the purpose of inducing security holders to give, revoke, or withhold a proxy with respect to a matter to be acted upon by security holders of an issuer . . . by any person who has solicited or intends to solicit proxies . . . may involve a solicitation within the meaning of the regulation, depending upon the particular facts and circumstances.”); see also 1992 Amendments, supra note 43, at 48,278 n.22 (explaining that SEC’s 1956 definition amendment clearly “was principally concerned with communications ‘by any person who has solicited or intends to solicit proxies’ prior to the formal commencement of the solicitation”).↑

511992 Amendments, supra note 43, at 48,277.↑

52Id.↑

53Id. at 48,278.↑

54Id. at 48,279.↑

55See id. (“A regulatory scheme that inserted [SEC] staff and corporate management into every exchange and conversation among shareholders, their advisors and other parties on matters subject to a vote certainly would raise serious questions under the free speech clause of the First Amendment, particularly where no proxy authority is being solicited by such persons.”).↑

56Id. at 48,278.↑

571992 Amendments, supra note 43. After the U.S. Supreme Court recognized commercial speech as protected under the First Amendment in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc., 425 U.S. 748, 762, 96 S. Ct. 1817, 48 L. Ed. 2d 346 (1976), some predicted a “collision” between the First Amendment and securities regulation. See, e.g., Frederick Schauer, The Boundaries of the First Amendment: A Preliminary Exploration of Constitutional Salience, 117 HARV. L. REV. 1765, 1780 (2004) (“Starting in the early 1980s, claims that the entire scheme of securities regulation needed to be tested against First Amendment standards became more common.”); Karl M. F. Lockhart, Note, A ‘Corporate Democracy’?: Freedom of Speech and the SEC, 104 VA. L. REV. 1593, 1625 (2018).

Amid debate in the 1980s and early 1990s about the First Amendment’s application to securities regulation, some scholars focused on the free speech concerns stemming from proxy solicitation regulation. See, e.g., Aleta G. Estreicher, Securities Regulation and the First Amendment, 24 GA. L. REV. 223, 314 (1990) (explaining that SEC’s “expansive definition” of solicitation overregulates expressive communications that “make no mention of proxies, proxy contests or upcoming shareholder meetings”); Clark A. Remington, Note, A Political Speech Exception to the Regulation of Proxy Solicitations, 86 COLUM. L. REV. 1453, 1468-71, 1474 (1986) (arguing that when a “proxy solicitation addresses a matter of public or political concern” it requires greater constitutional protection). As previously discussed, the SEC adopted the 1992 amendments in part to address such First Amendment concerns. See Lockhart, supra, at 1626. And any expected surge in First Amendment challenges to proxy solicitation regulation never occurred. Id. at 1625-27.↑

58The Division argues that in Meidinger v. Koniag, Inc., 31 P.3d 77, 84-85 (Alaska 2001), we concluded that the Division’s proxy solicitation regulations were not vague or overbroad and therefore did not violate free speech protection under article I, section 5 of the Alaska Constitution. But what we said in that case was that the challenger — who was actively soliciting proxy votes to oppose an upcoming ballot proposition — had failed to support his free speech argument with any case law, and we therefore rejected his argument. Id. at 85. It is beyond dispute that reasonable state regulation of commercial speech is not completely barred by constitutional free speech protection. See id. at 85 n.18. That begs the question of the reach, or overreach, of a specific regulatory application.↑

59If the line between lawful proxy solicitation regulation and unlawful infringement of free speech regarding corporate governance is left unclear, then the regulation also fails to give fair notice of what conduct is required and prohibited. “Laws should give the ordinary citizen fair notice of what is and what is not prohibited. People should not be required to guess whether a certain course of conduct is one which is apt to subject them to criminal or serious civil penalties.” Alaska Pub. Offices Comm’n v. Stevens, 205 P.3d 321, 325-26 (Alaska 2009) (quoting VECO Int’l, Inc. v. Alaska Pub. Offices Comm’n, 753 P.2d 703, 714 (Alaska 1988)).↑

60See Estreicher, supra note 57, at 318 (“[W]hen no meeting has been scheduled, the issues are only beginning to take shape, and the speaker is seeking to influence views on corporate affairs rather than induce impending shareholder action, the state is shorn of the corporate suffrage justification for regulating intracorporate communications.”).↑

61The ALJ noted that “the parties did not offer persuasive authority on whether [advocating against] a type of proxy . . . qualifies as a solicitation.” (Emphasis in original.) Rather than question whether the Division’s interpretation was in fact reasonable, the ALJ simply assumed that the Division’s broad “definition of solicitation [was] therefore reasonable” based on a lack of contradictory authority. The ALJ thus concluded that Ahmasuk’s letter was “both a direct request to not execute a discretionary proxy” under 3 AAC 08.365(A) and “a communication reasonably calculated to result in the withholding of a discretionary proxy” under 3 AAC 08.365(B). The ALJ’s ultimate conclusion, however, relied only on subsection (B)’s “reasonably calculated” definition, and the superior court affirmed only on subsection (B).↑

623 AAC 08.365(16).↑

63Nothing in the record suggests that in February Ahmasuk knew or should have known that a competing proxy card would circulate in May. And the Division’s enforcement order against Ahmasuk was issued in March, well before the May proxy card circulated. The Division’s enforcement could not have been predicated on May’s then-unknown proxy card.↑

643 AAC 08.335(e)(2) (emphases added).↑

653 AAC 08.365(12).↑

66See supra note 37 and accompanying text.↑

67We reiterate that context and facts are key. Our decision should not be read to automatically extend beyond this context and these facts. “In every case we decide what we decide, and nothing more.” Planned Parenthood of the Great Nw. v. State, 375 P.3d 1122, 1135 (Alaska 2016).↑