“Standing here and looking far off into the Northwest, I see the Russian as he busily occupies himself in establishing seaports and towns and fortifications on the verge of this continent…and I can say, Go on, and build up your outposts all along the coast, even up to the Arctic Ocean — they will yet become the outposts of my own country.”

Remarks made by William H. Seward at the 1860 Republican Convention, St. Paul, Minnesota, on the future of Alaska.

Introduction

In certain fundamental respects, the history of western development is a history of the accumulation of capital. With the rise of capitalism in England, the demand for raw materials, land, and labor increased dramatically. Quickly outstripping England’s ability to obtain such resources within its own borders, the country’s new entrepreneurial leaders had to look elsewhere. In an effort to compete with Britain for world resources and markets, other European countries followed suit.

In the Alaskan Arctic, the search for capital accumulation largely followed this classic historic pattern. Russian penetration of Alaska effectively began in 1741 when Vitus Bering, a Dane on a mission for the Russian government to determine where Asia ended and America began, sailed across the Bering Strait from Siberia. Significantly, the survivors of this expedition returned with valuable fur seal and sea otter skins along with information regarding the habits of animal life among Alaska’s newly discovered Aleutian islands and offshore waters. With these pelts bringing very high prices on the world market, the Czarist regime recognized that it could expand its revenue considerably. In a few short years, large numbers of Russian traders began cruising these waters, conscripting Native Aleut labor and demanding from them annual tributes of fur.

While the Russians were pushing east into Alaska, the British were expanding west. Almost a century earlier, England, not unlike the government of Russia, had turned over vast territories of Central Canada to the Governor and Company of Adventurers – better known as the Hudson’s Bay Company. Protected and supported by the constabulary, this early corporation was able to extract conditions of exchange that generally resulted in a significant transfer of wealth from northern Canada back to England.

For the Russian leaders of this era, maintaining direct sovereignty over the land was secondary to expanding commercial operations. However, by the 1860s, even these ventures had become more difficult. Faced with a decline in fur bearing mammals, the Russian-American Company was in financial trouble. A recent war with the British in the Crimea had also drained the national treasury and defense of their newly obtained eastern possessions appeared less and less viable. To increase their liquidity and reduce their colonial responsibility, Russia offered to sell Alaska to the United States government for $7,200,000.

In the spring of 1867, without consulting the original occupants of the region or obtaining title through purchase or treaty, the sale was completed. The one brief reference made in the treaty to Alaska’s Native people addressed neither the issue of status, rights, or land ownership. It simply stated that “The uncivilized tribes will be subject to such laws and regulations as the United States may, from time to time, adopt in regard to aboriginal tribes in that country.” From that moment on, the threat to Alaska Native rights shifted from Russia to the United States. But it was not until the passing of the Alaska Statehood Act of 1958 that the issue was directly addressed by the U.S. Congress. This legislation, while acknowledging the right of Natives to lands they used and occupied, authorized the new state government to select for its own use 103 million acres from the Territory’s public domain. With each selection by the state, more Native lands were placed in jeopardy.

“What, if anything does the General Government owe the natives of Alaska, and in what form shall the payment be made? It is a problem great in its moral as well as in its practical aspects. Having largely destroyed their food supplies, altered their environment, and changed their standards and methods of life, what does a nation that has drawn products valued at $300,000,000 owe to the natives of Alaska? Will this nation pay its debt on this account?”

Remarks made in 1909 by Major General A. W. Greely, former senior military officer in the Territory, in his volume Handbook of Alaska.

Threats to Native Lands

The question of how to resolve the issue of Native rights to land was first presented to the U.S. Department of Interior’s Bureau of Land Management [BLM] in 1961 by Athabascan Indians living in the Minto Lakes region of Interior Alaska, south of the Arctic Circle. Seeing the site as potentially profitable for future oil production and immediately valuable as a recreation area, the state requested a large parcel of land near Minto Village. Further arrangements were made to build a new access road to the area for Fairbanks city residents and visiting sportsmen.

The Minto Athasbascans immediately filed a protest with the U.S. Department of Interior asking them to protect their rights by turning down the state’s application. Shortly thereafter, sportsmen, conservationists, biologists, and other interested parties joined in the debate. Finally, in 1963, all the groups involved sat down with state representatives to seek a solution. At this gathering, the Minto Village chief, Richard Frank, argued that the proposed recreational development would destroy the Native way of life and suggested that the project be undertaken elsewhere where increased hunting pressure would not threaten local subsistence. “A village is at stake,” he said. “Ask yourself this question: Is a recreation area worth the future of a village?”

No answer was forthcoming, everyone eventually acknowledging that the issue of who was to control the land could only be decided at the federal level. As the state continued selecting lands in other sections of Alaska, similar protests were filed by Nati ve villages and associations. In 1963 alone, one thousand Natives from 24 villages petitioned Interior Secretary Stewart Udall urging that he install a “land freeze” on all land transfers from the federal government to the state until Native rights had been clarified.

As pressure mounted on the federal government to resolve the issue of Native lands, Alaska’s congressional delegation in Washington put forward a number of proposals. Senator Ernest Gruening recommended that the problem be taken up by the U.S. Court of Claims. Senator Bartlett thought state land transfers should proceed without waiting for the land claims issue to be resolved – a proposition strongly endorsed by state officials. Leaders of the Association on American Indian Affairs, various religious groups, and similar supporters of Native American interests, urged that no land transfers be awarded until the claims were settled. But what was still missing in this increasingly national level debate was a forceful, articulate presentation from Alaska’s Native people themselves.

By 1965, several regional Native organizations, including the Tanana Chiefs and southwest Alaska Council of Village Presidents, the Fairbanks Native Association, and the Cook Inlet [Anchorage] Native Association had been formed to address common interests including land, village housing, education, welfare, and the need for improved health facilities.

A year later, at a meeting organized by a young Barrow Inupiat, Charles “Etok” Edwardsen Jr, the Arctic Slope Native Association came into being, the members of which immediately voted to place their claim on 58 million acres – virtually all the land north of the Brooks Range – based on aboriginal use and occupancy. Board members of the new Association were elected from Kaktovik, Point Hope, Anaktuvik, and other North Slope villages.

Then, in the fall of 1966, over 250 leaders from seventeen regional and local associations came together in the first state-wide meeting of Alaska Natives. Overcoming a long history of distrust, the Eskimo, Indian and Aleut representatives at this meeting unanimously recommended that a freeze be imposed on all federal lands until Native claims were resolved; that Congress enact legislation settling the claims; and that there be consultation with Natives at all levels prior to any congressional action.

In addition to gaining experience in how to overcome their differences, Native leaders at this conference also learned another important fact – that unity brings political recognition and strength. Astonished at the attention given the conference by well-known state politicians, one Native leader observed, “If any delegate was seen paying for his own meal, it was probably because he chose to dine alone!” Next year, following a series of additional meetings, the Alaska Federation of Natives [AFN] was formally brought into being, with offices located in Anchorage. While problems of cultural differences, distinct languages, regional vested interests, and limited funding would continue to plague the new organization, it was nevertheless able to provide a convincing united voice in the effort of Alaska’s Natives to achieve a land claims settlement from the U.S. Congress.

Land Freeze

The first positive breakthrough for the Native population occurred later in 1966, when Interior secretary Udall imposed a “land freeze” on all federal land transfers to the state until Congress acted on the claims issue. Aghast, the governor of Alaska filed a lawsuit requiring Secretary Udall to transfer lands to the state. Concurrently, further claims were made by other Native villages and associations. By 1967, 20 percent more Alaska land had been claimed than actually existed! Given the seriousness of the impass, federal action had to be taken. In the summer of 1967, two bills were introduced to Congress to resolve the issue. One was sponsored by the Department of Interior. The other had the support of the Alaska Federation of Natives. Both requested money and land, but the former authorized a maximum of 50,000 acres per village while the latter made no mention of a maximum, the actual amount to be determined by the subsistence needs of the particular people in question.

The state, too, faced a potentially severe crisis. State revenues were declining, partly because the freeze prevented the issuance of oil leases on federal lands from which it was to receive 90 percent of federal revenue. It also recognized the growing political importance of the AFN and that Native claims would precede the obtaining of their remaining public domain lands. Thus, Governor Hickel proposed that the two work together to achieve a satisfactory settlement for both. The resulting state/AFN Land Claims Task Force report recommended that 40 million acres of land be conveyed to Native villages in fee simple [full legal ownership]; that all lands used for hunting and fishing continue to be available for that purpose for one hundred years; that the Native Allottment Act remain in force; that 10 percent of income from oil sales/leases of certain lands be paid to Natives the total of which would be at least $65 million; and that the settlement be carried out by business corporations organized by villages and regions.

Senator Gruening introduced the new Task Force bill into Congress in 1968 and arranged for public hearings by the senate Interior Committee to be held in Anchorage. Encouraged to attend by the AFN and the Native-run Tundra Times, villagers from Barrow in the north to Ketchikan in the southeast selected spokespeople to attend the hearings. The resulting speeches by Natives from across the state were consistent in demanding rights to their land.

Major opposition came from the Alaska Sportsmen’s Council and the Alaska Miner’s Association. The former objected to the granting of land but approved a cash settlement. The spokesman for the latter association was opposed to both, stating that “…neither the United States, the State of Alaska, nor any of us here gathered as individuals owes the Natives one acre of ground or one cent of the taxpayer’s money.” Underlying the sportsmen’s opposition was the threat of reduced access to hunting and fishing lands, whether for individual or commercial interest. Miners and others averse to a land settlement feared that the loss of 40 million acres would dramatically reduce opportunities for the state’s future economic development. No one, however, was fully prepared for the momentous oil discovery that was soon to occur hundreds of miles to the northeast, or how that event would reshape the whole debate over Alaska’s land and the future of its people.

Discovery of Oil

Following World War II, the U.S. oil industry instituted an extensive search for Alaskan petroleum. In 1957, at Swanson River on the Kenai Peninsula not far from Anchorage, it succeeded. Richfield Oil corporation drilled an important commercial well that was soon producing 900 barrels per day. This discovery – along with other encouraging petroleum and gas explorations – was crucial in helping convince Congress that the territory did indeed have the economic potential to become the 49th state.

In the next decade, geologists explored most of Alaska’s federal and state lands including those on the North Slope. Then, in the winter of 1965-66, after obtaining approval from the state, Exxon and Atlantic Richfield Oil companies flew in oil drilling equipment to an isolated inland site 330 miles north of Fairbanks. There in January of 1967, they drilled 13,517 feet without success. Pushing 60 miles further northward, a second well was drilled at Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic coast. On December 26th, 1967, in 30 degree below zero weather, an Exxon geologist recalled what happened next: “We could hear the roar of natural gas like four jumbo jets flying right overhead…as flare from a two- inch pipe shot at least 30 feet straight into that wind. It was a mighty encouraging sign that something big was down below.” That something big was oil-rich sadlerochit sand that had been deposited 200 million years before when the North Slope was a tropical wilderness. It represented the largest petroleum deposit ever encountered in North America, with an estimate of 9.6 billion barrels of recoverable oil.

The Emerging Role of the Alaska Federation of Natives

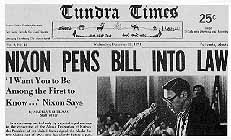

The discovery of oil on Alaska’s North Slope brought an entirely new perspective to the debate over the “land freeze.” and its relation to Native Land Claims. If the two were separated, oil-rich areas could be developed with lessened regard to the claims issue. If the freeze remained in place, petroleum and gas would remain untapped. Thus, depending on one’s political and economic perspective, major attention was focused on either supporting or removing the freeze. With the 1968 election of Republican Richard Nixon to the presidency, Walter Hickel, Alaskan governor and successful commercial developer, was nominated to become Secretary of Interior. Hickel, a vocal critic of the freeze, was in turn viewed negatively by powerful conservation groups and their influential Washington lobbyists. To receive confirmation as Interior secretary, he needed a broader base of support. The AFN, in turn, would give theirs only if Hickel agreed to continuing the freeze until the claims issue was resolved. Hickel finally agreed and was later confirmed. The AFN had obtained another victory in its efforts to obtain greater political influence.

At this time, the Federation further enhanced its national image by obtaining former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg and former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark as key legal advisors. This, however, caused considerable dismay within the ranks of the AFN, particularly among staff lawyers who had long represented regional Native interests. During this earlier period, the ability of the AFN to resolve its internal contradictions had been based largely on an understanding whereby Board members meeting in Anchorage regularly consulted with regional lawyers. Following these contacts, proposals were then ratified at meetings of regional associations prior to any action being taken by the AFN Board. Though cumbersome, it was compatible with the Native value placed on consensus. But when Justice Goldberg was brought on the team, lawyers for the regional associations voiced strong public opposition, feeling their interests and those of their regions would be reduced in importance – an evaluation of some substance.

Similar changes were taking place within the Native leadership itself. In the beginning, regional associations were basically “grass-roots” organizations, formed by local villager leaders as a means of resisting serious threats to their subsistence-oriented way of life. Then, with the emergence of the AFN, the struggles became increasingly complex. At this point, more highly educated urban-based Natives began moving into positions of leadership. Several of these new leaders had previously attended Mt. Edgecumbe or other government-run Native residential boarding high schools. Such shared experiences not only gave them a broader perspective on the world, but enhanced their ability to work together in tackling the numerous issues arising within the AFN. Others had received their initial leadership training in new federally funded programs such as Alaska’s Rural Community Action Programs, or RuralCAPs.

Still, these new leaders faced an almost overwhelming set of responsibilities for which they had little preparation. Maintaining regular contact with federal and state politicians in Alaska and Washington D.C., participating in congressional hearings, giving speeches to Chambers of Commerce and similar groups, and negotiating conflicts between the AFN and regional associations, provided little time to deepen their understanding of the outlook and needs of their largely rural-based constituents. Travel funds too were limited. Eventually, as their links to regional and national seats of power strengthened, their ties to the villages diminished – a process that would lead to serious difficulties later on.

As the struggle to obtain a claims settlement continued, the AFN stepped up its campaign to reach sympathetic supporters sensitive to the needs of Alaska Natives. The civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s had attuned many to the problems of poverty and systematic discrimination against America’s non-European minority populations. By means of new lobbying organizations, press releases, television appearances, speeches, and publications, Americans also came to learn that the Eskimo, Indian, and Aleut, who claimed over two-thirds of Alaska, owned outright less than 500 acres and held in restricted title only an additional 15,000 acres. While 900 Native families shared the use of four million acres in 23 reserves run by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, all other rural Native families lived on the public domain. For Native subsistence-oriented villagers, minimal cash income combined with the high cost of goods, had resulted in an exceedingly low standard of living – lower than that of many dispossessed sharecroppers living in the deep south.

The late 1960s was an era of intense organization by many grass-roots constituencies seeking improved civil rights, Native rights, women’s rights, and environmental quality; all competing for limited federal and state resources. Thus, the call of Alaska’s Native leaders at this time was only one among many – each challenging the American people to reevaluate the country’s political, economic, and environmental goals, priorities, and actions.

Competing Discourses on Development

In the state, conflicting issues came together in late August of 1969 at the 20th Alaska Science Conference, a division of the prestigious American Association for the Advancement of Science. Held on the campus of the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, the conference leaders had chosen as their theme: The Impact of Oil on the Future of Alaska. This broad perspective grew out of problems of the previous 1968 meeting which had been the target of protests by student dissidents frustrated with the physical scientists seeming lack of interest in social and environmental issues. In part to counter the possibility of renewed demonstrations, several well-known social scientists from within and outside the state were invited to speak on the politics of petroleum, public policy and the environment, the ecological impact of Arctic development, and similar topics of a volatile nature. The conference was also scheduled for the week prior to the state sale of North Slope oil leases in Anchorage. An almost unbelievable figure of one billion dollars was on many people’s lips as the amount the oil companies might have to bid for rights to drill at Prudhoe Bay. A state rich in resources but poor in cash was about to receive a phenomenal windfall.

The first invited speaker, Robert Engler, a well-known critic of the oil industry, warned of the negative impact of oil corporations on the state’s political, economic and social institutions. He argued that wherever these enterprises have functioned, their concentrated economic power over the community, the most massive of any industry in the world, has been forged into political power as well. Law, public bureaucracies, political machinery, foreign policy, and public opinion, he said, have all been “harnessed for the private privileges of the international brotherhood of oil merchants. ” By various means, public relations specialists, lobbyists, and lawyers have kept the spotlight away from the penetrating powers of oil; focusing instead “…on the mystique of petroleum technology, corporate benevolence, and the possibility for an amenable public to be cut in on “something for nothing.”

A rejoinder to Engler’s presentation was given by Frank Ikard, president of the American Petroleum Institute, the industry’s key trade and lobbying organization. Ikard spoke of the oil industry’s desire to work together with the citizens of the state in a joint venture that would enhance the lives of all concerned. Other oil company representatives addressed the need for a favorable price and tax structure if “a great and lasting oil industry here in Alaska can be developed. James Galloway, vice-president of Humble Oil, [a joint owner with Atlantic Richfield company of the discovered well at Prudhoe Bay], addressed the environmental issue saying that some Arctic land had to be torn up to get the oil out. “Let’s not fool ourselves,” Galloway reminded his audience. “This activity is far past the point of return.”

Conservationists from the Sierra Club and similar organizations responded sharply, reminding the participants that Congress was about to pass the National Environmental Policy Act that required the government to make a detailed public list of any adverse environmental effects of every project in which it was involved before action could be taken. Underlying much of the debate that followed was the question of whether Alaska could control the recovery of oil or whether the oil industry would end up controlling Alaska. United States senator Ted Stevens, throwing away his prepared speech, spoke heatedly at the debate unfolding before him, saying, with appropriate gestures, “I am up to here with people who tell us how to develop our country.” Federal regulations were not needed to govern construction of the proposed pipeline to Prudhoe Bay, Stevens told his audience. Such proposals suggesting that Alaskans were not to be trusted in managing their own affairs were “stupid, absolutely stupid.” Compromises were also proposed suggesting that the state was new enough and rich enough to build its economy and use its resources “in ways that will not produce derelict landscapes.”

Shortly thereafter, John Borbridge Jr, AFN vice-president and the lone Native participant, addressed the conference. Speaking articulately and with considerable intensity, he cautioned both the audience and the attending press:

For the most part you have easily gotten used to the Alaska Native, because he had needed your help and your assistance, and a fairly large, complex “industry” has emerged based on his needs. The relationship between one who gives and one who receives when it has been institutionalized is very easy to accept, to adjust to and to forget. As long as the arrangement is accepted or tolerated, there is nothing that is disconcerting in this relationship. But what happens as the Alaska Native assumes his rightful place as an equal partner in the economic, political and other power structures of this state? What happens when instead of coming in and asking for help, he comes in by right and asserts his right to share equally in the opportunities and benefits of economic and social development?

The conclusion of his presentation was met with a brief sprinkling of polite applause. It was clear that an aggressive calling for equal rights by a Native northerner could stir less than enthusiastic responses in Alaska as elsewhere.

More significant in these debates was the implicit assumption that the land – including tundra and forest, federal parks and wildlife refuges – belonged to the federal government and the state and by extension, its various citizens. It was if the claims of Alaska’s Natives to the land were non-existent – or at least an inappropriate topic for discussion at a scientific meeting. And yet, without a resolution of this issue, other struggles over petroleum development and environmental protection would have to wait.

On September 10th, 1969, a week after the conference ended, the state of Alaska offered its petroleum lease sale on lands it had claimed in the Prudhoe Bay region. When the bidding was over, competing oil companies had paid over $900 million to the state for the right to drill on selected lands. For many members of Congress, this major financial windfall to the state placed the whole land claims settlement issue in a new light. No longer did earlier monetary settlement proposals appear so high. The sale further demonstrated to Congress that the state could easily afford to share some of its mineral revenues with its Native people. But on that September day outside the hotel where the sale was taking place, Charlie Edwardsen, Jr. from Barrow, and other supporters calling themselves Concerned Alaska Native Citizens, carried picket signs and handed out leaflets proclaiming that “We are once again being cheated and robbed of our lands,” and stop the “Two billion dollar Native land robbery.” Under the watchful eyes of both the Anchorage police and local reporters, the AFN president was asked what he thought of such efforts. They did not have the support of the “official Native organization,” was his carefully phrased reply.

During the fall, state officials and private developers continued arguing over how best to develop Alaska. At a meeting organized by the state Legislative Council, Arlon Tussing, a young economist associated with the University of Alaska, offered an alternative view challenging the predominant theme of the day. Speaking at a well-attended Brookings Institution seminar, Tussing reminded his audience that “There is a philosophy of development for development’s sake and almost everybody at this seminar shares that philosophy to one degree or another. But this is a set of attitudes peculiar to certain classes of people – businessmen, politicians, and upper level civil servants, economists and the like…The majority of Alaskans may not be for development for development’s sake; most villages are not, nor are the oil workers on the Slope, nor fishermen…I even suspect that most of the 15 to 20-year old children of the people here have little use for that philosophy.”

At this same time, Alaska Natives intensified their own internal debate over the question of land rights. The North Slope Inupiat were especially distraught over reports of the state Division of Lands approving the mooring of an oil company barge at the site of a Native home and cemetery. Using this event as an illustration, the Arctic Slope Native Association argued strongly that the AFN must take a more militant stand. Finally, in February, 1970, AFN president Emil Notti made a speech that mentioned the possibility of establishing a `Native Nation.’ “If Congress cannot pass a bill that we think is fair, then …we will petition Congress and the United States to set up a separate Indian nation in the western half of Alaska.” Barrow leader Eben Hopson, commenting in the northern Native Tundra Times newspaper on the background to Notti’s threat said, “It took him a long time to express himself in this manner…to perhaps fall into the same line that the Arctic Slope Native Association has been advocating all the time.”

Elsewhere in the state, Natives were becoming increasingly frustrated over threats to their land. In hearing after hearing with government officials and in conversations with their own leaders, they argued that the land was theirs as it had been for centuries. They also anticipated receiving cash compensation from a claims settlement that could be used to stimulate economic development at the local level and enhance their Native cultural integrity. Additionally, they sought ways to deal with growing social problems in the villages. And finally, they wanted greater political self-determination.

Given the volatility of Native American protests occurring across the nation at this time, many of them focusing on federal government collusion with energy corporations, President Richard Nixon was led to proclaim his own policy of “Indian self- determination.” However, his definition was quite opposite to that espoused by most Native Americans including those residing in Alaska. Marvin Franklin, an “American of Indian descent,” executive with the Phillips Petroleum Company, and acting Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs [BIA] in the early 1970s, supported Nixon’s proposal:

The psychology of the Indian is not mysterious and not too unlike that of other Americans. He wants a chance to put his skills to work and he wants more of a voice in his own affairs. His special handicap – let’s call it a mixed blessing and handicap – is his inherited Indian culture. It has given him a straitjacket that makes it tough for him to compete on equal terms with his fellow citizens.

The new program [of the BIA] will turn over to tribal government, as rapidly as possible, a maximum amount of administration for Indian affairs. Minimum control will be retained in Washington; policy will be set there, but administration of that policy will be in the hands of tribal representatives or Bureau superintendents. [italics added]

Basically, the government’s “self-determination” policy as reflected in the statements of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, meant that tribal governments and villages had reached the stage whereby they could carry out decisions made in Washington. Needless to say, this was quite different from the concept of self-determination held by Native Americans in Alaska and elsewhere that promoted the creation of democratic self-governing Native villages and regions.

Later in the year, another bill put before Congress was also challenged by the Federation. Proposing a billion dollar settlement for the extinguishment of all land claims within the state, formal title would be given to only 10 million acres, far less than that considered necessary for subsistence, let alone economic self-sufficiency.

Other serious limitations included the possible termination within five years of BIA educational and social programs, their responsibilities to be turned over to the state for as long as the latter saw fit to fund and administer them. By contrast, the House subcommmittee on Indian Affairs proposed an alternative settlement involving 40 million acres of land. This was more satisfactory. But could the financial settlement offered by the Senate bill be combined with the land settlement proposed by the House?

There were other unresolved problems too, such as compensation for loss of aboriginal rights to fish and wildlife resources. Should such claims be specifically addressed in the settlement act? What conflicts were likely to emerge with the state over subsistence hunting and fishing on state land? After several Congresional hearings, three Alaska governors [Egan, Hickel, and Miller] affirmed that “the subsistence needs and reliance upon these resources by Alaska Natives would be met by the state of Alaska.” Congress then put aside the subsistence issue, not wishing to set in place any new law that might possible challenge the sensitive balance of legislative jurisdiction over fish and wildlife resources earlier established between the western states and Native American tribes residing in that region.

Finally, there was the question of how to distribute settlement monies and land. All executive and legislative leaders wanted to solve the claims issue as quickly as possible so that future litigation would not interrupt construction of the trans-Alaska pipeline. Secretary Hickel proposed a grant of 500 million dollars. Senator Henry Jackson, chairman of the Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, and Representative Wayne Aspinall, chairman of the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, were willing to include land, but they had no interest in seeing the BIA reservation system extended to Alaska. Rather, they and other Congressmen wanted Alaska’s Natives to become more actively assimilated into mainstream America. Out of this perspective came the proposal that Native profit-making corporations be the means to achieve the settlement.

AFN leaders had no interest in Hickel’s proposed distribution of cash since it disregarded the need for subsistence land. Furthermore, past history elsewhere suggested that a large scale distribution of funds might quickly be dissipated. Nor was there much enthusiasm for receiving the land “in trust,” to be bureaucratically administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Some AFN leaders, including Vice President John Borbridge. Jr., were drawn to the suggestion that land previously held communally, would be adapted to modern conditions by utilizing a corporate approach. Furthermore, Don Wright, then AFN president, was informed that any proposed AFN alternative involving traditional governments or Indian Reorganization Act [IRA] Councils would be actively discouraged by Congress. Thus, while some argued for the corporate scheme, other AFN leaders merely felt obliged to support it.

This was not true, however, of the Arctic Slope Native Association. Their leaders had a different strategy. Well aware of Congress’ scheme to use profit-making corporations as the means for receiving settlement monies and lands, they put forward an alternative proposal urging that the land be owned “tribally” [i.e., collectively] through the medium of regional IRA Councils.

The major strength of the Arctic Slope Native Association’s IRA regional plan was that Native land, held “in trust” by the federal government, could never be lost through stock transfer, corporate sale, hostile takeover, or non-payment of taxes. In the minds of those making the proposal, this was of great significance since, as the villagers had stated so many times before, the land represented both the spirit and substance of their culture. It was something to be shared rather than individually owned. It was where their ancestors lived; where they grew up; and where their grandchildren would later reside. It was further suggested that the wildlife it contained was a renewable resource on which they could always depend. Thus, it provided both a cultural and economic bond between generations reaching back into the past and projecting forward into the future. As long as the people and the land were one, the culture would survive. If the two became separated, the culture might wither and die.

Who Should Own the Land?

Acknowledging the importance of safeguarding the land, most AFN leaders nevertheless were strongly opposed to the idea that the IRA be the means to achieve it. To protect the land was one thing. To have it permanently held “in trust” by an a bureaucratic Bureau of Indian Affairs was another.

The lure of corporate power and wealth also held considerable appeal to Native leaders who had been frustrated by years of poverty. If the claims settlement meant opening the door to the economic mainstream and enjoying its increased standard of living, then it was time to learn how to use the tools of that structure. While the corporate model had its problems, its appeal to the large majority of AFN leaders remained substantial.

Thus, most urban-based Native leaders saw the land as “the key to a brighter future.” As expressed by Emil Notti, AFN’s first president, in corporate hands the land could enable the Native Alaskans to ‘actively participate in the new economic development of the state.’ In similar manner, cash compensation flowing to the regional corporations could provide scholarships and in other ways assist shareholders be more effective in adapting to modern economic conditions.

For these reasons, the AFN leadership eventually accepted the corporate model as the best means for managing the land and money expected from the settlement. Turning then to the highly charged question of how such settlement monies and lands were to be distributed, a decision was made that the initial dispersal of funds should be allocated according to the population size of the 12 regions.

However, the Arctic Slope Native Association was so opposed to this latter proposal that it withdrew from the AFN – the executive director Charlie Edwardsen Jr, specifically accusing the organization of promoting “welfare legislation” rather than a land settlement. Only if the regions with the most land area were to receive the largest amount of land and money, would the ASNA rejoin the Federation. As Joe Upicksoun, Association president, explained to the leaders of the other regions: “We realize each of you has pride in his own land. By accident of nature, right now the eyes of the nation and the world are centered on the North Slope…Without intending to belittle your land, the real reason for the entire settlement is the oil, which by accident is on our land, not yours.”

After further discussion, the AFN offered to revise its plan and the Arctic Slope Association rejoined the negotiation process. Under the new proposal, money received from Congress was to be divided by size of land lost through the extinguishment of title, while funds from future mineral developments would be shared among the regions. Given this arrangement, the Arctic Slope would retain half of the revenues it received from mineral development and distribute the remainder to other regions based on size of population.

Finally, by 1971, it appeared that most parties in the debate were ready to seek a resolution. The one additional factor required to shape the final settlement was the support of the petroleum industry. Given the large financial commitment made in oil exploration and bidding, the companies were anxious to see a return on their investment. When their efforts to build a transAlaska pipeline from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez on Alaska’s southwestern coast were blocked by new Native claims, the industry realized that its future profits were dependent on the land question being resolved. Working closely with the White House and in conjunction with the AFN, they allied themselves with the Native movement. Shortly thereafter, a congressional resolution was at hand.

In April of 1971, President Richard Nixon proposed to Congress a settlement in which Alaska Natives were to receive 44 million acres of land, $500 million in compensation from the federal treasury, and an additional $500 million in mineral revenues from lands to which title was to be extinguished. Major recipients would be 12 regional corporations. After a summer of writing, both the Senate and House passed separate bills in support of the president’s proposal. Following a final conference committee review to resolve differences between the two bills, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was passed.

Nixon, knowing that several provisions, such as the issue of taxation, had been opposed by the AFN, wanted a symbolic statement of Native support. The AFN then called a meeting of 600 delegates. At the conclusion of a lively debate, they voted overwhelmingly in support of the bill. The one Native association delegate voting no was from the Arctic Slope. The “no” vote was in opposition to Congress’ decision to use size of population as the key criteria for the allocation of land and money rather than size and value of the land. In a letter sent to President Nixon just prior to the signing of the act, the Association’s president and executive director stated: The only method that “…even begins to approach to type of allocation a court would make, [is one] which would take into consideration not only the size of the area claimed, but its value.” Rejecting the appeal by the Arctic Slope Native Association, President Nixon signed the bill into law on December 18, 1971.

The Land Claims Settlement Act of 1971

In the final version of the Settlement Act, Native claims to almost all of Alaska were extinguished in exchange for approximately one-ninth of the state’s land plus $962.5 million in compensation. Of the latter, $462.5 million was to come from the federal treasury and the rest from oil revenue-sharing. Settlement benefits would accrue to those with at least one-fourth Native ancestory. Of the approximately 80,000 Natives enrolled under ANCSA, those living in villages [approximately 2/3rds of the total] would receive 100 shares in both a village and a regional corporation. The remaining 1/3rd would be “at large” shareholders with 100 shares in a regional corporation plus additional rights to revenue from regional mineral and timber resources. The Alaska Native Allotment Act was revoked and as yet unborn Native children were excluded. The twelve regional corporations within the state would administer the settlement. A thirteenth corporation composed of Natives who had left the state would receive monies but not land.

Along with cash compensation, these corporations could also earn income from their investments. However, the drafting of the bill did not clarify whether the corporations were expected to redistribute the proceeds from their investment income to their shareholders or whether they could keep them for further investment. A “shared wealth” provision of the Act [Section 7(i)], stipulated that 70 percent of income received by regional corporations from their resources were to be shared annually with the other corporations. To protect the land from estrangement, no Native corporate shares could be sold to non-Natives for 20 years – until 1991 – at which time all special restrictions would be removed. Then, non-Natives would be eligible to become shareholders, lands would be liable for taxation by the state, and the regionals would be open to the possibility of hostile takeovers.

Under the supervision of the regionals, village level corporations would also select lands and administer local monies received under the settlement act. Although village corporations could choose to be non-profit entities if they so wished, all selected the profit-making category.

With the President’s signature on the settlement act, the relationship between the Native peoples of Alaska and the land was completely transformed. No longer was ownership directly linked to Native government. Instead, by conveying land title to the 12 regional corporations and 200 local village ones chartered under the laws of the state of Alaska, all ties to traditional or IRA “tribal” governments were bypassed. With the President’s signature, Native Alaskans whose earlier use and occupancy had made them co-owners of shared land, now became shareholders in corporate-owned land.

To what extent did this legislation reflect the hopes and aspirations of Alaska’s Native population? At the time of passage, most Native people were unaware of the complexities of the bill, but looked forward to having their own land and additional monies that could be used to improve their low standard of living. Alaska Federation of Native leaders were enthusiastic at the large settlement, feeling they had achieved a considerable accomplishment under highly adverse conditions. The limitations in the bill stemmed primarily from pressures placed on them by the government and petroleum industry forcing them to make compromises not of their choosing. They also saw the corporate solution both as a way to remove themselves from the bureaucratic yoke of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and as a new tool in the struggle to maintain their culture.

Not all, however, took an optimistic view. Critics feared that eventually the regionals could become conduits for larger multi-national corporations, enabling the latter to take over valuable lands and resources currently held in Native hands. Loss of this land would then be followed by destruction of Native culture and the rise of new class divisions mirroring those of the larger society. By this means, the government’s long term goal of assimilating Alaska’s Native population into the larger mainstream would finally be achieved. As summed up by Fred Bigjim, an Inupiat educator from Nome who had once been a close aide of Eben Hopson, “What is happening to Native people in Alaska is not a new story; it is a new chapter in an old story.”

Still, whether one supported the bill or opposed it, all agreed that the implications of the land claims settlement for Alaska’s Natives were profound. Given the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, even more pronounced changes were to occur on the North Slope. Due to this circumstance, the Inupiat and other Alaska Natives were able to bring into being a unique development strategy – one which combined elements of both adaptation and resistance to the steadily mounting pressures impinging on them from what they formerly referred to as the world “outside.”

Originally published on http://arcticcircle.uconn.edu/SEEJ/Landclaims/ancsa1.html – the website went offline January 1, 2009.